As we move deeper into the digital age, a ticking time bomb lurks within countless computer systems worldwide. The year 2038 problem represents a significant technical challenge that could affect everything from smartphones to industrial control systems. Unlike the Y2K bug that captured global attention at the turn of the millennium, this issue stems from a fundamental limitation in how many computer systems track time. Understanding this problem and its potential impact is crucial for developers, IT professionals, and anyone who relies on technology in their daily lives.

Understanding Unix Time: The Foundation of Digital Timekeeping

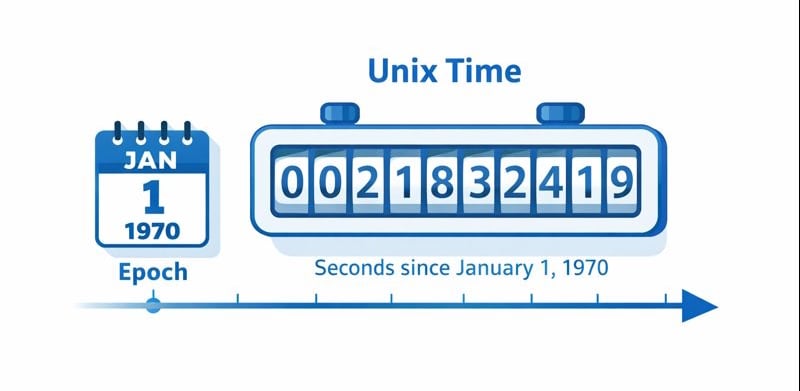

To grasp the year 2038 problem, you first need to understand how computers track time. Most modern systems use something called Unix time, a timekeeping method that counts the number of seconds that have passed since January 1, 1970, at 00:00:00 UTC. This date is known as the Unix epoch.

Think of it like a giant stopwatch that started running on New Year's Day 1970 and has been counting every second since then. When you check the time on your computer or smartphone, the system calculates the current date and time by taking this second count and converting it into a readable format. This elegant system has worked remarkably well for decades, powering everything from email timestamps to financial transactions.

The simplicity of Unix time made it incredibly popular among programmers. Instead of tracking years, months, days, hours, and minutes separately, systems only need to store and manipulate a single number. This approach saves memory and makes time calculations straightforward.

The Technical Problem: When the Clock Runs Out

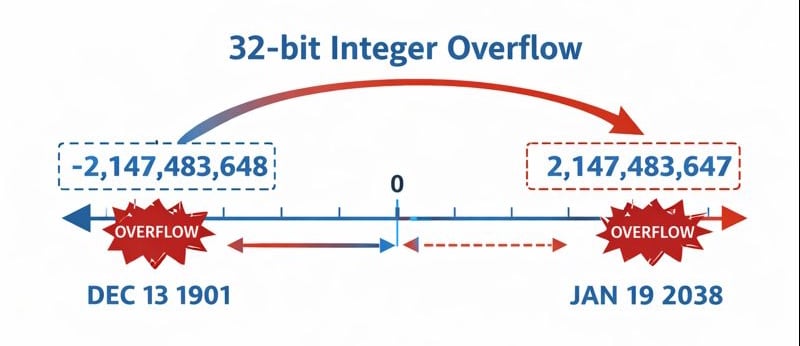

The year 2038 problem occurs because many systems store this second count as a 32-bit signed integer. In computing terms, a 32-bit signed integer can hold values ranging from -2,147,483,648 to 2,147,483,647. This gives us roughly 68 years of positive values to work with.

The crisis point arrives on January 19, 2038, at precisely 03:14:07 UTC. At this moment, the Unix time counter will reach 2,147,483,647 seconds. When the next second ticks over, the system attempts to increment to 2,147,483,648, but this exceeds what a 32-bit signed integer can store. The result is an integer overflow.

What Happens During an Integer Overflow?

When an integer overflow occurs, the number doesn't simply stop counting. Instead, it wraps around to the lowest possible value, which is -2,147,483,648. In practical terms, affected systems will suddenly think the date is December 13, 1901, more than a century in the past.

Imagine a car odometer that only has five digits. When it reaches 99,999 miles and you drive one more mile, it rolls back to 00,000. The same principle applies here, except instead of displaying zero, the system jumps to a date from the early 1900s.

This sudden time jump can cause catastrophic failures. Software might crash, databases could become corrupted, security certificates will fail, and automated systems might malfunction. Any program that relies on accurate timestamps or performs date calculations could experience serious errors.

Real-World Impact: Which Systems Are at Risk?

The year 2038 problem isn't just a theoretical concern. Numerous systems still rely on 32-bit time representations, and the consequences could be far-reaching.

Embedded Systems and IoT Devices

Perhaps the most vulnerable category includes embedded systems and Internet of Things devices. These systems often use 32-bit processors and run firmware that's difficult or impossible to update. Think of smart home devices, industrial sensors, medical equipment, and automotive systems. Many of these devices are designed to operate for decades, meaning they'll still be in use when 2038 arrives.

Legacy Software and Infrastructure

Countless businesses still run critical operations on legacy software written decades ago. Banking systems, insurance databases, and government infrastructure often include components that haven't been updated in years. If these systems use 32-bit timestamps, they'll need significant overhauls before the deadline.

Financial and Legal Systems

Financial institutions routinely work with future dates for mortgages, bonds, and long-term contracts. A 30-year mortgage issued in 2025 extends well past 2038. Systems processing these transactions need to handle dates beyond the 32-bit limit. Legal documents, patents, and contracts with expiration dates past 2038 also require properly functioning timestamp systems.

Systems Most at Risk:

- Embedded devices with 32-bit processors and unchangeable firmware

- Legacy banking and financial software systems

- Industrial control systems and infrastructure management

- Medical devices designed for long-term deployment

- Transportation and logistics tracking systems

Solutions and Progress: Moving Toward 64-Bit Time

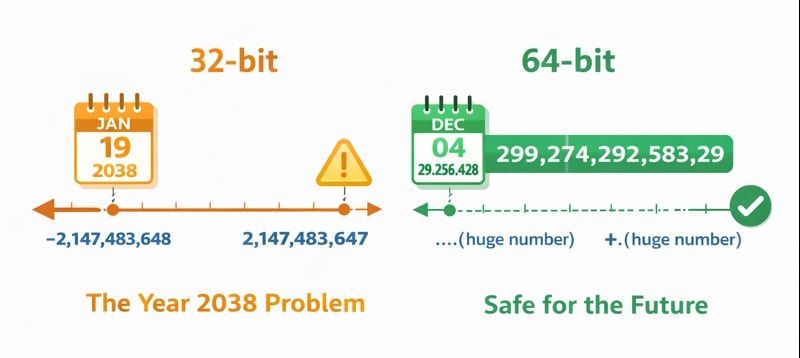

The good news is that the technology industry recognized this problem years ago and has been working on solutions. The primary fix involves transitioning from 32-bit to 64-bit timestamps.

A 64-bit signed integer can represent time values far into the future, approximately 292 billion years from the Unix epoch. This effectively solves the problem for any conceivable human timescale. Most modern operating systems, including current versions of Linux, Windows, and macOS, have already implemented 64-bit time support.

Current Status of Mitigation Efforts

Major technology companies and open-source projects have been addressing this issue for over a decade. The Linux kernel added support for 64-bit time in 32-bit systems through recent updates. Programming languages and database systems have introduced functions and data types that handle extended time ranges.

However, the transition isn't automatic. Developers must actively update their code to use these new time functions. Organizations need to audit their systems, identify vulnerable components, and plan upgrades or replacements. This process takes time, resources, and careful testing to avoid introducing new problems.

Comparing to Y2K: Lessons Learned

Many people draw parallels between the year 2038 problem and the Y2K bug. Both involve date-related technical limitations, and both require widespread system updates. However, there are important differences.

The Y2K problem affected virtually all computer systems because two-digit year representations were nearly universal. The 2038 issue is more selective, primarily affecting systems using 32-bit Unix time. Additionally, we have more time to prepare and a clearer understanding of which systems are vulnerable.

The Y2K experience taught the industry valuable lessons about proactive system maintenance and the importance of addressing known technical limitations before they become crises. Many organizations are applying these lessons to their 2038 preparations.

Key Takeaways:

- The year 2038 problem occurs when 32-bit systems can no longer count Unix time seconds past 2,147,483,647

- Affected systems will experience integer overflow, potentially causing crashes, data corruption, and system failures

- Embedded devices, legacy software, and long-term financial systems face the highest risk

- The solution involves transitioning to 64-bit timestamps, which extends the time range by billions of years

- Organizations should audit their systems now and plan upgrades to avoid disruption

What Developers and Organizations Should Do Now

If you're a developer or IT professional, now is the time to take action. Start by auditing your codebase and systems to identify any use of 32-bit time representations. Look for legacy code, third-party libraries, and embedded systems that might be vulnerable.

Test your applications with dates beyond January 19, 2038. Many systems allow you to manually set the system clock forward to verify behavior. Document any components that fail these tests and prioritize them for updates.

For embedded systems and IoT devices, check with manufacturers about firmware updates or replacement timelines. If devices can't be updated, plan for their replacement before 2038. Consider the full lifecycle of any new systems you deploy to ensure they'll remain functional past the critical date.

Organizations should include year 2038 compliance in their technology planning and procurement processes. When evaluating new software or hardware, verify that it uses 64-bit time representations. Build this requirement into vendor contracts and service agreements.

Conclusion

The year 2038 problem represents a real but manageable challenge for the technology industry. Unlike sudden security vulnerabilities or unexpected hardware failures, we have the luxury of time to prepare. The technical solution exists and has been implemented in most modern systems. The remaining work involves systematic identification and remediation of vulnerable systems before the deadline arrives. By understanding the problem, recognizing which systems are at risk, and taking proactive steps now, we can prevent the year 2038 problem from becoming a crisis. The key is not to ignore this issue or assume someone else will fix it, but to take responsibility for the systems we build and maintain.

FAQ

No, the year 2038 problem is unlikely to cause widespread catastrophic failures like some feared with Y2K. Most modern systems have already transitioned to 64-bit timestamps, and the technology industry has been aware of this issue for years. However, specific vulnerable systems, particularly embedded devices and legacy software, could experience serious problems if not addressed. The key difference from Y2K is that we have better tools, more awareness, and a clear technical solution already implemented in most platforms.

Modern smartphones and computers running current operating systems are generally protected from the year 2038 problem. iOS, Android, Windows, and macOS have all implemented 64-bit time support. However, older devices still in use in 2038, particularly those running outdated operating systems or 32-bit processors, could experience issues. The bigger concern is apps and software that might still use 32-bit time functions even on modern hardware.

You can test your software by setting your system clock to a date after January 19, 2038, and observing how your applications behave. For code-level checking, look for uses of 32-bit time types like time_t on older systems, or examine how your code stores and manipulates timestamps. Review any third-party libraries and dependencies for their time handling implementations. Consider using static analysis tools that can identify potential year 2038 vulnerabilities in your codebase.

Financial services, healthcare, manufacturing, transportation, and utilities face the highest risk because they rely heavily on embedded systems and legacy infrastructure. Banks processing long-term mortgages and bonds, hospitals with medical devices designed for decades of use, factories with industrial control systems, and power plants with monitoring equipment all need to address this issue. Government agencies managing long-term records and defense systems with aging infrastructure are also prioritizing year 2038 remediation.

Technically yes, but not for approximately 292 billion years. A 64-bit signed integer can count seconds until roughly the year 292,277,026,596. This timeframe extends far beyond any practical human concern, well past the expected lifespan of our sun and Earth itself. By the time this becomes relevant, computing technology will have evolved in ways we cannot currently imagine, making this effectively a permanent solution to the Unix time limitation problem.