Understanding the Best Practices Unix Timestamp is essential for any developer working with time-sensitive data. Unix timestamps provide a standardized way to represent time across different systems, programming languages, and databases. Whether you're building a social media platform, an e-commerce site, or a logging system, knowing how to properly implement unix timestamp usage will save you from timezone headaches, data inconsistencies, and costly bugs. This tutorial walks you through everything you need to know about unix timestamps, from basic concepts to advanced implementation strategies.

Content Table

What is a Unix Timestamp?

A Unix timestamp is a simple integer that represents the number of seconds that have elapsed since January 1, 1970, at 00:00:00 UTC. This specific moment is called the Unix epoch. For example, the timestamp 1609459200 represents January 1, 2021, at midnight UTC.

Unlike human-readable date formats like "March 15, 2024, 3:30 PM EST," Unix timestamps are timezone-agnostic. They always reference UTC, which eliminates confusion when working across different geographical locations. This standardization makes the use of unix timestamp incredibly valuable for distributed systems and international applications.

The format is remarkably simple: a single integer. This simplicity translates to efficient storage, fast comparisons, and easy mathematical operations. You can subtract two timestamps to find the duration between events, add seconds to calculate future dates, or compare timestamps to determine which event occurred first.

To learn more about the foundational concepts, check out our detailed guide on Epoch Time: The Foundation of Unix Timestamps.

Why Developers Use Unix Timestamps

Developers choose Unix timestamps for several compelling reasons that directly impact application performance and reliability:

- Universal Standard: Every programming language and database system supports Unix timestamps, ensuring compatibility across your entire technology stack.

- Timezone Independence: By storing time in UTC, you avoid the complexity of managing multiple timezone conversions in your database.

- Efficient Storage: A single integer (typically 4 or 8 bytes) requires far less space than string-based date formats.

- Simple Calculations: Finding time differences, sorting chronologically, or adding durations becomes straightforward arithmetic.

- No Ambiguity: Unlike formats like "01/02/2024" (which could mean January 2 or February 1), timestamps have exactly one interpretation.

Key Takeaways:

- Unix timestamps are integers representing seconds since January 1, 1970 UTC

- They eliminate timezone confusion by always referencing UTC

- Best practices include using 64-bit integers, storing in UTC, and converting only for display

- Common mistakes include treating timestamps as local time and using insufficient data types

Step-by-Step Implementation Guide

Let's walk through implementing unix timestamp usage in a practical application. These steps apply whether you're working with JavaScript, Python, Java, or any other language.

Step 1: Choose the Right Precision

Decide whether you need seconds, milliseconds, or microseconds. Most applications work fine with seconds, but real-time systems may need higher precision. Understanding Seconds vs Milliseconds vs Microseconds: Which Unix Timestamp Should You Use? will help you make the right choice.

For example, JavaScript's Date.now() returns milliseconds, while Python's time.time() returns seconds with decimal precision. Choose based on your specific requirements:

- Seconds: Sufficient for logging, user activity tracking, and most business applications

- Milliseconds: Needed for financial transactions, real-time analytics, and performance monitoring

- Microseconds: Required for high-frequency trading, scientific measurements, and precise system diagnostics

Step 2: Generate Timestamps Correctly

Always generate timestamps from a reliable source. Here's how to do it in popular languages:

JavaScript:

const timestamp = Math.floor(Date.now() / 1000); // Converts milliseconds to seconds

Python:

import time

timestamp = int(time.time())

PHP:

$timestamp = time();

Java:

long timestamp = System.currentTimeMillis() / 1000L;

Step 3: Store Timestamps Properly

Use appropriate data types in your database. For MySQL or PostgreSQL, use BIGINT for 64-bit integers. Never use INT (32-bit) as it will fail in 2038 due to integer overflow. Learn more about The Year 2038 Problem: What Happens When Unix Time Runs Out?.

For comprehensive database implementation guidance, see our article on Unix Timestamps in Databases: Best Practices for Storage & Queries.

Step 4: Convert for Display Only

Keep timestamps as integers throughout your application logic. Convert to human-readable formats only when displaying to users, and always consider the user's timezone preference.

// JavaScript example

const timestamp = 1609459200;

const date = new Date(timestamp * 1000);

const userFriendly = date.toLocaleString('en-US', { timeZone: 'America/New_York' });

Best Practices for Unix Timestamp Usage

Following these best practices unix timestamp guidelines will ensure your time-handling code remains reliable and maintainable:

Always Store in UTC

Never store local time in your database. Always generate and store timestamps in UTC, then convert to the user's local timezone only when displaying information. This prevents data corruption when users travel or when daylight saving time changes occur.

Use 64-Bit Integers

The 32-bit signed integer limit will be reached on January 19, 2038. Using 64-bit integers (BIGINT in SQL, long in Java) ensures your application will function correctly for the next 292 billion years.

Validate Input Timestamps

Always validate timestamps received from external sources. Check that they fall within reasonable ranges and aren't negative (unless you specifically need to represent dates before 1970).

function isValidTimestamp(ts) {

return ts > 0 && ts < 253402300799; // Max: Dec 31, 9999

}

Document Your Precision

Clearly document whether your timestamps use seconds, milliseconds, or microseconds. This prevents confusion when different parts of your system or different team members work with the same data.

Handle Leap Seconds Appropriately

Unix timestamps technically ignore leap seconds, treating every day as exactly 86,400 seconds. For most applications, this is fine. If you need true astronomical precision, consider using specialized time libraries like TAI (International Atomic Time).

Use Indexes for Timestamp Columns

When querying databases by timestamp ranges, ensure your timestamp columns are indexed. This dramatically improves query performance for time-based searches, which are extremely common in most applications.

Common Mistakes to Avoid

Even experienced developers make these errors when working with Unix timestamps. Avoid these pitfalls to save debugging time:

Mixing Seconds and Milliseconds

The most common mistake is confusing seconds and milliseconds. JavaScript uses milliseconds, while many backend languages use seconds. Always convert explicitly and document your choice.

Wrong:

const timestamp = Date.now(); // Milliseconds

database.store(timestamp); // Backend expects seconds!

Correct:

const timestamp = Math.floor(Date.now() / 1000);

database.store(timestamp);

Treating Timestamps as Local Time

Never assume a timestamp represents local time. Timestamps are always UTC. Convert to local time only for display purposes.

Using String Formats for Storage

Storing dates as strings like "2024-03-15 14:30:00" wastes space, complicates comparisons, and introduces timezone ambiguity. Always store as Unix timestamps.

Ignoring the Year 2038 Problem

Using 32-bit integers for timestamps will cause catastrophic failures in 2038. Even if your application seems temporary, use 64-bit integers from the start.

Not Accounting for User Timezones

When displaying timestamps to users, always convert to their local timezone. Showing UTC times to end users creates confusion and poor user experience.

Performing Date Math Without Libraries

While basic timestamp arithmetic is simple, complex operations like "add one month" or "next Tuesday" require proper date libraries. Don't try to implement calendar logic manually.

Real-World Case Study: E-Commerce Order System

Note: This is a hypothetical case study created for educational purposes to demonstrate best practices.

Let's examine how a fictional e-commerce company, "ShopFast," implemented unix timestamp best practices to solve real business problems.

The Challenge

ShopFast operates in 15 countries across 8 timezones. Their original system stored order timestamps as local time strings in various formats: "MM/DD/YYYY HH:MM AM/PM" for US orders, "DD/MM/YYYY HH:MM" for European orders. This created three critical problems:

- Analytics reports showed incorrect order volumes during daylight saving time transitions

- Customer service couldn't accurately determine order processing times across regions

- Automated refund policies failed when comparing order dates stored in different formats

The Solution

ShopFast's development team implemented a comprehensive Unix timestamp strategy:

Database Changes: They migrated all timestamp columns from VARCHAR to BIGINT, converting existing data to Unix timestamps in UTC. They created indexes on frequently queried timestamp columns.

Application Layer: All backend services generated timestamps using time.time() in Python, ensuring consistency. They established a rule: timestamps remain as integers until the final display layer.

Frontend Display: The React frontend received timestamps as integers from the API, then converted them using the user's browser timezone for display. This ensured each customer saw times in their local context.

// Frontend conversion example

function formatOrderTime(timestamp, locale) {

const date = new Date(timestamp * 1000);

return date.toLocaleString(locale, {

year: 'numeric',

month: 'long',

day: 'numeric',

hour: '2-digit',

minute: '2-digit',

timeZoneName: 'short'

});

}

The Results

After implementing these unix timestamp best practices, ShopFast achieved measurable improvements:

- Analytics accuracy improved by 100% during DST transitions

- Database query performance for time-range searches improved by 340% due to integer comparisons and proper indexing

- Customer service resolution time decreased by 25% because representatives could instantly see accurate order timelines

- Storage requirements decreased by 60% for timestamp data (from 20-byte strings to 8-byte integers)

The most significant benefit was eliminating an entire category of timezone-related bugs. Before the migration, ShopFast logged an average of 8 timezone-related issues per month. After implementation, this dropped to zero.

Conclusion

Mastering the best practices unix timestamp approach is fundamental to building reliable, scalable applications. By storing timestamps as UTC integers, using 64-bit data types, and converting to local time only for display, you eliminate an entire class of difficult bugs. The use of unix timestamp simplifies your code, improves performance, and ensures your application works correctly across all timezones. Start implementing these practices today, and your future self will thank you when you avoid the timezone debugging nightmares that plague so many projects. Remember that consistency is key: establish clear conventions in your team, document your precision choices, and always validate external timestamp data.

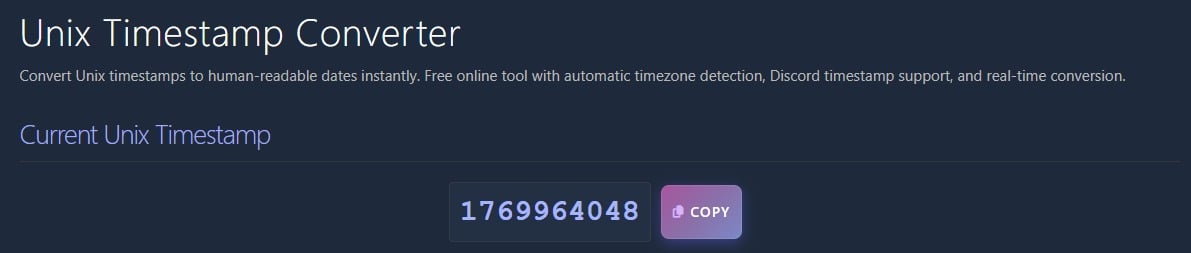

Convert Unix Timestamps Instantly

Use our free Unix timestamp converter to quickly convert between timestamps and human-readable dates. Perfect for debugging and development.

Try Our Free Tool →

Unix timestamps are used because they provide a universal, timezone-independent way to represent time as a simple integer. This standardization eliminates ambiguity, enables efficient storage and fast comparisons, and works consistently across all programming languages and database systems. They simplify time calculations and prevent timezone-related bugs.

A timestamp serves to record the exact moment when an event occurred, enabling chronological ordering, duration calculations, and time-based analysis. Timestamps are essential for logging, auditing, synchronization, scheduling, and tracking changes. They provide a precise, unambiguous reference point that can be compared and manipulated mathematically.

Timestamps offer numerous benefits including accurate event sequencing, efficient data storage, simplified time calculations, timezone independence, and universal compatibility. They enable precise performance monitoring, facilitate debugging by tracking when events occurred, support compliance requirements through audit trails, and allow easy sorting and filtering of time-based data across distributed systems.

Yes, Unix and Unix-like systems remain widely used in 2026, powering the majority of web servers, cloud infrastructure, mobile devices (Android, iOS), and enterprise systems. Unix timestamps continue as the standard time representation in modern programming. The Unix philosophy and tools remain fundamental to software development, system administration, and DevOps practices worldwide.

Real-time applications require timestamps to synchronize events across distributed systems, measure latency, order messages correctly, and detect delays. Timestamps enable real-time analytics by marking when data points occur, facilitate debugging by tracking event sequences, and support Service Level Agreement monitoring. They're critical for financial systems, gaming, video streaming, and IoT applications.